Early Beginnings/First Ever Prototype (1976)

CHECK OUT FLOYD’S OWN VERSION OF THE STORY AT FLOYDROSE.COM

Floyd, like many guitarists around this era in, felt like the typical Fender and Les Paul weren’t cutting it for the musical style they wanted to perform. For Floyd, he often fought with his 1950s strat to do Jimi Hendrix style tremolo tricks. Of course, the standard Fender tremolo could only handle so much before it went out of tune. He wanted something bullet-proof, consistent, and full-sounding without the worry of tuning between songs or sets. And hence, experimentation begun to take place.

Floyd realized that the key was preventing movement of the strings at the nut. His epiphany moment was using superglue to lock the string at the nut, which actually worked until the glue gave out. Upon this realization, Floyd Rose, a Jewelry maker with metals experience, started experimentation and eventually came up with a relatively raw design made of brass.

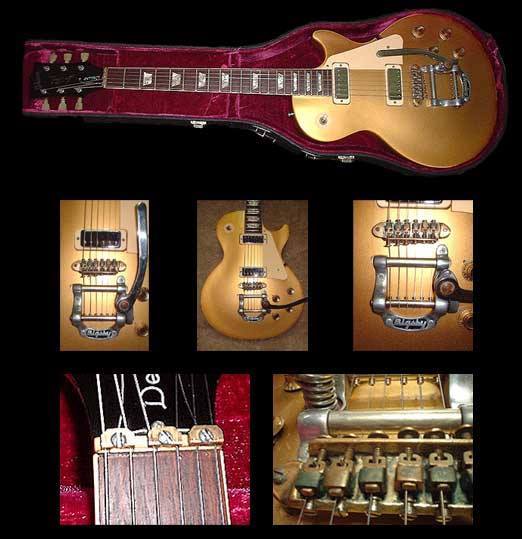

Above is a Les Paul fitted with the very first Floyd Rose prototype put on a guitar. This guitar has the first Floyd Rose ever made (from what I’ve read). It’s a stock 1970 LP deluxe with a factory Bigsby used by Greg Golden, one of Floyd Rose’s friends and bandmates at the time. Floyd and Greg played together in bands throughout the 1970s. This guitar is currently on display at “Bizarre Guitars” in Reno, Nevada.

The design was rather primitive but perhaps worked well. It was made of brass, which is a softer metal and didn’t hold up as well as steel. The locking nut is rather interesting and crude, but of course, the theory worked perfectly. This is the first design, and Greg Golden actually recorded with Floyd using this guitar on a song.

From here, Floyd got serious and started working on the Patent Prototype and later the FRT-1.

Above is a recent picture of Floyd Rose (left) and Greg Golden (right)

Above is Billy Duffy – lead guitarist of “The Cult” (left), Floyd Rose (middle), and Greg Golden (right).

With perfect timing, a tremolo-friendly music scene, and a new Kramer deal with Eddie Van Halen, the Floyd Rose tremolo exploded in sales and ruled the market throughout the 1980s. In fact, so many competitors tried to copy the tremolo that Floyd had to immediately use licensing agreements. The tremolo went through many redesigns in early production, much of it hidden history I cover in this website.

Floyd, a talent musician himself, was actually part of a band called “Q5” and a few others.

Floyd Rose is on the far left.

Another song from the second album by Q5 in 1986.

Music Radar gave a great interview with Floyd Rose regarding the early history, which you can read here.

Everything below comes from Music Radar:

A rare discussion with one of the electric guitar’s leading innovators

Floyd Rose ad #1

Floyd Rose ad #2

Floyd Rose ad #3

Such tenuous associations allow us to share an interview we conducted a few months ago with Floyd Rose himself. He tells about the development of the system from its very first incarnation, how he feels about the licensed version of his design and the impact a certain Eddie Van Halen had – both on his business and on music itself.

Les Paul, Leo Fender, Seth Lover, Jim Marshall… the catalogue of inventors that have genuinely altered the course of the electric guitar and its associated music is, if you actually chew it over for a while, a fairly short one. However, any list that doesn’t include the name of Floyd Rose is an incomplete one. His creation – an innovative type of guitar bridge and nut that securely locked the strings at both ends – hit the streets with an almost mythical sense of timing: it coincided with the emergence of a four-piece band, blasting out of Pasadena, California, and history was baying to be inscribed onto the slabs of time. The band was Van Halen and the invention was shortly to become the double-locking tremolo system.

“Oh yeah, Eddie (Van Halen) was the driving force, especially in the advertising,” concedes Floyd over a freakishly clear transatlantic phone line. “Many people ask if this would have happened without Eddie and I think it would have, but certainly not as quickly. I think guitar players wanted to stay in tune, but Eddie’s power and popularity at the time made it explode onto the scene.”

Floyd is a little fuzzy on the exact date of the genesis of the concept of the Floyd Rose tremolo system, but it’s certain that he filed for his very first patent towards the end of the seventies…

“I’m not very good at timelines, being 61 now, but I started when I was 28 I think,” Floyd laughs.

That makes it 1976 by our shaky subtraction and there are so many conflicting accounts of the bridge in the public domain that we’re grateful to be able to take our opportunity to ask him how it all started.”How much detail do you want?” he asks us with what we’re certain is a knowing raise of the eyebrows. “All of it? Okay…

“Well, being in a rock band myself and being a big fan of Hendrix and Deep Purple, using the whammy was something I wanted to do, only I’m real finicky about being in tune when I play,” he begins. “All the tricks that we used just weren’t good enough for me, lubricating the nut, aligning the strings, using fewer winds around the peg, that type of thing.

“My first modification [Floyd played a Strat back then – Ed] was to loosen the six screws the bridge rocks on in front so I could get more range, and I also had the 1/4-inch bar [arm]. To my dismay that increased range just made it more unstable. I like to start a song with a whammy bar effect but so often you’d come in on the first chord and it was like… horrible!

“So, one night after practice I got back home and I was watching TV while noodling on guitar. I had the nut kinda close to my head and as I pushed the bar down I noticed that the windings on the low E string slid across the nut.”It just came to me that that was the problem, so I got a pen and marked the string, went down on the bar, let it come back under spring tension and sure enough that string didn’t come back into position. So I figured that, if friction’s the problem, the answer was to remove it completely: no friction, no movement.

“So I got some Krazy Glue, glued the string after it was tuned, went down slowly and sure enough it worked for a while, until the glue let go. Boom, it came back in tune… well, at least that string did!”This all sounds like something any of us might do in an idle moment, but the next step would rely not only on Floyd’s inventiveness and inspiration, but his engineering skill too.

“At the time I was making jewellery so I had a lapidary rig – you use it to cut stones and silver – and I took a piece of brass and made the first nut which had three little U-shaped clamps and a hole through it,” he continues. “I put it on my ’57 Strat neck, which is of course sacrilege – every time a collector hears that, they just cringe – but I wanted it to stay in tune. I was real careful too, so I made sure it fitted into the original nut slot – it was maybe just a little bit wider than 1/4 inch – and all I did was drill two holes underneath where the nut would sit. So I started using it and, as long as I didn’t go too deep on the bar, it was fine.

“So from there I needed a stronger one that’d hold the strings, so the next version I designed I had made at a machine shop: it cost me $600! I had to borrow the money from my parents, but it worked pretty well. I started the learning process of metalworking and hardening, the fact that the steel on the strings dents the metal after you clamp a few times, so it stops working.”

Floyd considers this as the very first version of what would become the familiar double-locking system. The second version included both a locking nut and a new bridge, with the third featuring an improved bridge design. Floyd takes up the story.

“The progression was set in place and when I showed it to a few people, of course they wanted one. The second guy I sold one to was Randy Hansen, an amazing Hendrix impersonator.

Randy Hansen © Gernot W. Freudenberger

“That version didn’t have tuners on the bridge, but it didn’t need it since I hand-made them and I would hand-sand the lip of the nut clamps so that when they went down in the rails they couldn’t twist when you tightened the wrench. When we started to mass produce them, you couldn’t really make them that accurately any more so that’s when I started to think that there had to be a way to tune it after it was clamped. That’s when I invented the version with the fine tuners.

As we continue to chat, Eddie Van Halen’s name starts to crop up with increasing regularity. VH’s kinetic debut hit the streets in 1977, and even then the guitarist was looking for a way to keep his guitar in tune. Perfect timing, see?

“A friend of mine, Linn Ellsworth of Boogie Bodies guitars, was making guitars for Eddie at the time so I went with him to show Eddie the tremolo. He liked it and gave me a guitar to put one on, which was the one without fine tuners, the fourth version.”

Eddie Van Halen (c) © Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis

How about the EVH Signature Floyd Rose bridge that is fitted to the latest version of the Wolfgang?

“Well, he always wanted to have his name on it and I wouldn’t agree to that; I wanted my name on it!” laughs Floyd. “But on the one he’s using, his version, we let him put his name on it as a ‘thank you’ to him for his part. That version is made like the originals.”

Was there any other player at the time that had a hand in increasing the trem’s profile?

“Well, there was [Journey guitarist] Neal Schon… I would sell these by going to big concerts and I would get backstage,” Floyd says. “I learned real quick that if I asked to speak to anyone from the band, you didn’t get anywhere, so I asked to speak to the guitar tech for the guy and of course he’s all excited. So I would show them first and they would show the artist, and that’s how I got in.

“Neal saw it and wanted one put on his Les Paul, and he gave me one that he said he’d never liked the sound of. I brought it back to him and it became one of his favourites as I’d taken so much wood out of it the sound had changed.

Neal Schon © Larry Marano /Retna Ltd./Corbis

“As ever, there are original Floyds and there are derivatives, some officially licensed and others… not so. How does Floyd feel about the whole licensing trend?

“Well, if it doesn’t say Floyd Rose on it, then it’s not a real Floyd Rose, y’know?” he says simply. “The way that came about was when I went with Kramer we needed bridges right away, because Eddie was endorsing and we were getting tons of orders.

“When I got all the patents secured and Kramer started selling guitars like crazy with tremolo on them, the other companies started copying. So we had to go visit them and then, because of that, we had a big discussion about how to address the problem – we couldn’t just constantly sue everybody – so Kramer CEO Dennis Beradi and I made a deal that other companies could license and make the bridges.

“Of course, when we did that deal we just didn’t think that approving the quality mattered at the time – it was just impossible to police. That’s how the licensing thing came along and we felt that we could sell the companies that cared the original as an OEM piece.

Steve Vai © Radu Sigheti/Reuters/Corbis

“Again, people immediately wanted to put them on lower-priced guitars, so they went to manufacturers in Asia, but the quality… they didn’t know how to make one. The metal hardening is critical and they didn’t know how to do it, so the bridges failed pretty easily.”

The answer is simple: get the right tool for the right job and, although there are myriad licensed versions of the tremolo available, we can’t recommend strongly enough that an original has to be the one to opt for…”